Infectious disease is a leading cause of death worldwide, especially among children, according to the World Health Organization. Children in developing nations are particularly vulnerable, and while substantial progress has been made in reducing the childhood mortality rate, disparities still exist across regions, countries, and socioeconomic statuses.

As a pediatric neurosurgeon, Penn State’s Steven Schiff has dedicated a significant portion of his career to the study and treatment of infectious disease, particularly brain diseases in children. Now, Dr. Schiff aims to apply innovative prediction models, similar to those used in forecasting the weather, in order to provide improved personalized treatment to patients battling infectious disease. Ultimately, the same strategies can be used for targeted prevention strategies for such infections.

Steven Schiff, Professor; Director, Penn State Center for Neural Engineering; Associate, Institute for Cyber Science; Member, Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences

COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING

Harvey F. Brush Chair, Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics

COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

Department of Neurosurgery

“The goal is to learn in order to predict. We want to get to a point where physicians who are treating infected patients can ask ‘where are you from?’ and in the case of infants, ‘when did the baby get sick?’

With those two bits of information and using surveillance modeling, we can then guide point of care treatments in real time.”

Transforming Personalized Treatment

Today, patients suffering from symptoms of infectious disease such as sepsis, flu-like illness, fever with rash, or meningitis, are typically all treated alike: by drawing samples for laboratory analysis, starting antibiotic therapy with the physician’s best guess as to the likely causes, and then hoping to learn the causative reason for the infection over a period of days from laboratory analysis.

Dr. Schiff’s vision is to move from reactive, delayed diagnoses to real-time treatment guidance using predictive models that incorporate historical microbiological surveillance data, geographic location of the patients, as well as environmental and climatic factors to determine the likely pathogens in order to narrow down the best treatment choices at the point of care.

“We have demonstrated that it is feasible to predict epidemic disease outbreaks from retrospective seasonal and geographical case data and have shown that we can take climate factors into account in our predictive models,” says Dr. Schiff. “But such predictive strategies have never been used in treatment of individual patients. We believe our approach to predictive personalized public health has the potential to substantially improve patient outcomes.”

This vision builds off of an extensive body of work by Dr. Schiff in infant hydrocephalus, which is fluid build-up in the brain as a result of infection that can lead to brain damage and death. In areas like Uganda and sub-Saharan Africa, infectious disease is the cause for the majority of cases of hydrocephalus which are estimated at about 100,000 to 200,000 cases each year. Factors such as rainfall play a significant role in the prevalence of many infectious diseases, so linking observations in weather patterns to patterns of epidemics and outbreaks seems logical.

“Infant hydrocephalus is the most common reason for neurosurgery in young children worldwide,” said Dr. Schiff. “If we are to best treat infectious disease, for example in these infants, we need to start focusing on preventing their infections, instead of training surgeons and building advanced surgical facilities to repair the effects after these infections occur. We didn’t plan to study the climate, but we realized we needed this information to study infections.”

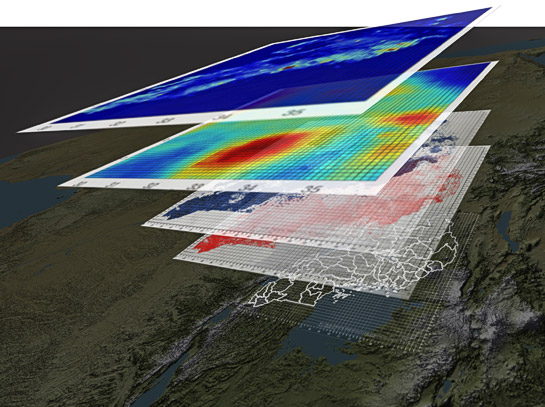

Using multi-pronged approach spanning epidemiology, meteorology, and genomics, the team will employ a variety of tools including machine learning, statistics, and engineering control theory to build maps—similar to weather maps—in order to create an understanding that not only looks at disease outbreak, but informs treatment at point of care.

Layered view of different types of maps used by Schiff and his colleagues.

“We believe our approach to predictive personalized public health has the potential to substantially improve patient outcomes.”

An emphasis in the creation of this technology has been its intended use in impoverished nations. By working with local government officials and policymakers in Uganda, Dr. Schiff and his team are aiming to create a solution that is both portable and able to be implemented anywhere, regardless of the region’s infrastructure.

Collaboration Meets Cutting-Edge Research

A significant indicator of the potential impact of the project and the impetus for its launch was an $8.1 million Transformative award from the Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) High-Risk, High-Reward Program. This follows an additional NIH Director’s Pioneer award Dr. Schiff received in 2015, which allowed him to shift his professional focus from neuroscience to study the causes of childhood infectious diseases in the developing world. Combined, these awards have placed Penn State among just a few institutions with faculty who have received both.

For Dr. Schiff, the awards point to a trend of groundbreaking research taking place at the University to address issues of global importance.

“All my life, all I ever wanted to do is mix science and medicine,” says Dr. Schiff. “Having both of these awards going at Penn State makes us just one of a small handful of universities doing this kind of cutting-edge work.”

In addition to close collaboration with a multitude of partners from across the University in disciplines including meteorology, engineering, mathematics, statistics, and computational biology, as well as a partnership with Penn State’s Institute for Personalized Medicine and Penn State Health, Dr. Schiff emphasizes that a multitude of perspectives and resources are required to in order to venture into such groundbreaking territory.

“One of our unique strengths at Penn State is the ability to integrate across traditional disciplines with the teamwork required to work toward important goals,” says Dr. Schiff. “Faculty at Penn State are very open to such collaborations, and across our medical, engineering and science campuses, we have the breadth of expertise required to tackle critical problems of this magnitude.”

As part of Penn State’s College of Medicine, the Institute for Personalized Medicine focuses on applying the tools of modern genomics to infectious disease onset and patient response to treatments. In addition to cutting-edge genomics capabilities, the institute also boasts a variety of bioinformatics and biostatistics services that include analysis, prediction, and software support.

According to James Broach, director of the institute, the potential for this project is realized in the ability of this interdisciplinary team to synthesize and analyze large data sets.

“We ask ourselves, ‘how do we handle large data sets, interrogate large data sets, but more importantly, how do we merge very different types of data to come up with an answer that no single data set alone can solve,’” says Dr. Broach. “If we can connect particular disease outbreaks to particular locations and environmental conditions—or any other variable for that matter—then the ability to mount the appropriate response quickly, rather than waiting until you discover that this particular agent is responsible for this particular outbreak, could really improve public health in a major way.”

“One of our unique strengths at Penn State is the ability to integrate across traditional disciplines with the teamwork required to work toward important goals. Faculty at Penn State are very open to such collaborations.”

Beyond Penn State, the team is closely collaborating with the CURE Children’s Hospital of Uganda, in addition to leading experts from Harvard, Columbia, Washington University of St. Louis, and George Mason University. The Ugandan National Planning Authority, Meteorological Authority, and Ministry of Health, are also among the critical departments that are collaborating on this project, and Dr. Schiff noted that the work of these agencies within Uganda will be key to successful implementation trials.

“This is work that no one could ever do on their own. It is the outgrowth of twelve years at Penn State and the opportunity to collaborate through transdisciplinary research with colleagues and personnel in Uganda— blending medicine, engineering and science,” Dr. Schiff said.

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) High-Risk, High-Reward grant will allow Penn State’s Steven Schiff and team to explore a radically changed approach to predicting, preventing and treating infectious disease at the individual level at point-of-care. This venture provides the researchers an opportunity to explore a new way of addressing critical unmet needs, especially in the developing world. (Penn State News, 10/2/18)

Penn State’s Institute for Personalized Medicine advances healthcare for the community through the use of modern technology and more effective tools. The institute applies translational and clinical research to personalized health care at Penn State, facilitates the incorporation of this research into patient care, and educates and advocates for the practice of personalized healthcare.